Basic of Eye Anatomy

Posted Under:

This is Basic of eye anatmoy! it will useful to doctors and medical students and science students!

This is Physiology of the Eye

Posted Under:

This video simply and useful to say about physiology of the eye!

Eye Quantel Medical Anatomy

Posted Under:

Hello freinds this is about eye anatomy,Quantel Medical proposes a 3D animation explaining the anatomy and function of the eye. Vision is a fundamental and particularly complex function provided by the visual system. Main element of this system, the eye is often compared to a camera. So the eye can be described as a dark room equipped of a double objective (cornea, crystalline lens), a focus (accommodation) and a diaphragm (pupil). His photographic film (retina) which will print the image, is scanned by a cable (optic nerve) and then interpreted by the brain. Find more information about the eye

Ultrasound, Nanoparticles May Help Diabetics Avoid the Needle

Posted Under:

This world has imporved with new technologies....A new nanotechnology-based technique for regulating blood sugar in diabetics may give patients the ability to release insulin painlessly using a small ultrasound device, allowing them to go days between injections -- rather than using needles to give themselves multiple insulin injections each day. The technique was developed by researchers at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

And This is hopefully a big step toward giving diabetics a more painless method of maintaining healthy blood sugar levels," says Dr. Zhen Gu, senior author of a paper on the research and an assistant professor in the joint biomedical engineering program at NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill.

The technique involves injecting biocompatible and biodegradable nanoparticles into a patient's skin. The nanoparticles are made out of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) and are filled with insulin.

Each of the PLGA nanoparticles is given either a positively charged coating made of chitosan (a biocompatible material normally found in shrimp shells), or a negatively charged coating made of alginate (a biocompatible material normally found in seaweed).

When the solution of coated nanoparticles is mixed together, the positively and negatively charged coatings are attracted to each other by electrostatic force to form a "nano-network." Once injected into the subcutaneous layer of the skin, that nano-network holds the nanoparticles together and prevents them from dispersing throughout the body.

Using the new technology developed by Gu's team, a diabetes patient doesn't have to inject a dose of insulin -- it's already there. Instead, patients can use a small, hand-held device to apply focused ultrasound waves to the site of the nano-network, painlessly releasing the insulin from its de facto reservoir into the bloodstream.

The researchers believe the technique works because the ultrasound waves excite microscopic gas bubbles in the tissue, temporarily disrupting nano-network in the subcutaneous layer of the skin. That disruption pushes the nanoparticles apart, relaxing the electrostatic force being exerted on the insulin in the reservoir. This allows the insulin to begin entering the bloodstream -- a process hastened by the effect of the ultrasound waves pushing on the insulin.

And This is hopefully a big step toward giving diabetics a more painless method of maintaining healthy blood sugar levels," says Dr. Zhen Gu, senior author of a paper on the research and an assistant professor in the joint biomedical engineering program at NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill.

The technique involves injecting biocompatible and biodegradable nanoparticles into a patient's skin. The nanoparticles are made out of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) and are filled with insulin.

Each of the PLGA nanoparticles is given either a positively charged coating made of chitosan (a biocompatible material normally found in shrimp shells), or a negatively charged coating made of alginate (a biocompatible material normally found in seaweed).

When the solution of coated nanoparticles is mixed together, the positively and negatively charged coatings are attracted to each other by electrostatic force to form a "nano-network." Once injected into the subcutaneous layer of the skin, that nano-network holds the nanoparticles together and prevents them from dispersing throughout the body.

Using the new technology developed by Gu's team, a diabetes patient doesn't have to inject a dose of insulin -- it's already there. Instead, patients can use a small, hand-held device to apply focused ultrasound waves to the site of the nano-network, painlessly releasing the insulin from its de facto reservoir into the bloodstream.

The researchers believe the technique works because the ultrasound waves excite microscopic gas bubbles in the tissue, temporarily disrupting nano-network in the subcutaneous layer of the skin. That disruption pushes the nanoparticles apart, relaxing the electrostatic force being exerted on the insulin in the reservoir. This allows the insulin to begin entering the bloodstream -- a process hastened by the effect of the ultrasound waves pushing on the insulin.

Thalamus

Posted Under:

Hey do you know? "Thalamus" is a important part of the Brain. The two thalami are located in the center of the brain, one beneath each cerebral hemisphere and next to the third ventricle.

Functionally the thalami can be thought of as relay stations for nerve impulses carrying sensory information into the brain; the thalami receive these sensory inputs as well as inputs from other parts of the brain and determine which of these signals to forward to the cerebral cortex.

Mach 1000 Shock Wave Lights Supernova Remnant

Posted Under:

What is the Mach 1000 Shock wave When a star explodes as a supernova, it shines brightly for a few weeks or months before fading away. Yet the material blasted outward from the explosion still glows hundreds or thousands of years later, forming a picturesque supernova remnant. What powers such long-lived brilliance?

In the case of Tycho's supernova remnant, astronomers have discovered that a reverse shock wave racing inward at Mach 1000 (1000 times the speed of sound) is heating the remnant and causing it to emit X-ray light.

"We wouldn't be able to study ancient supernova remnants without a reverse shock to light them up," says Hiroya Yamaguchi, who conducted this research at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA)

Modern astronomers know that the event Tycho and others observed was a Type Ia supernova, caused by the explosion of a white dwarf star. The explosion spewed elements like silicon and iron into space at speeds of more than 11 million miles per hour (5,000 km/s).

When that ejecta rammed into surrounding interstellar gas, it created a shock wave -- the equivalent of a cosmic "sonic boom." That shock wave continues to move outward today at about Mach 300. The interaction also created a violent "backwash" -- a reverse shock wave that speeds inward at Mach 1000.

"It's like the wave of brake lights that marches up a line of traffic after a fender-bender on a busy highway," explains CfA co-author Randall Smith.

In the case of Tycho's supernova remnant, astronomers have discovered that a reverse shock wave racing inward at Mach 1000 (1000 times the speed of sound) is heating the remnant and causing it to emit X-ray light.

"We wouldn't be able to study ancient supernova remnants without a reverse shock to light them up," says Hiroya Yamaguchi, who conducted this research at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA)

Modern astronomers know that the event Tycho and others observed was a Type Ia supernova, caused by the explosion of a white dwarf star. The explosion spewed elements like silicon and iron into space at speeds of more than 11 million miles per hour (5,000 km/s).

When that ejecta rammed into surrounding interstellar gas, it created a shock wave -- the equivalent of a cosmic "sonic boom." That shock wave continues to move outward today at about Mach 300. The interaction also created a violent "backwash" -- a reverse shock wave that speeds inward at Mach 1000.

"It's like the wave of brake lights that marches up a line of traffic after a fender-bender on a busy highway," explains CfA co-author Randall Smith.

Colossal New Predatory Dino Terrorized Early Tyrannosaurs

Posted Under:

Hey do you know? A new species of carnivorous dinosaur -- one of the three largest ever discovered in North America -- lived alongside and competed with small-bodied tyrannosaurs 98 million years ago.

This newly discovered species, Siats meekerorum, (pronounced see-atch) was the apex predator of its time, and kept tyrannosaurs from assuming top predator roles for millions of years.

Named after a cannibalistic man-eating monster from Ute tribal legend, Siats is a species of carcharodontosaur, a group of giant meat-eaters that includes some of the largest predatory dinosaurs ever discovered. The only other carcharodontosaur known from North America is Acrocanthosaurus, which roamed eastern North America more than 10 million years earlier. Siats is only the second carcharodontosaur ever discovered in North America; Acrocanthosaurus, discovered in 1950, was the first.

"It's been 63 years since a predator of this size has been named from North America," says Lindsay Zanno, a North Carolina State University paleontologist with a joint appointment at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, and lead author of a Nature Communications paper describing the find. "You can't imagine how thrilled we were to see the bones of this behemoth poking out of the hillside."

Zanno and colleague Peter Makovicky, from Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History, discovered the partial skeleton of the new predator in Utah's Cedar Mountain Formation in 2008. The species name acknowledges the Meeker family for its support of early career paleontologists at the Field Museum, including Zanno.

The recovered specimen belonged to an individual that would have been more than 30 feet long and weighed at least four tons. Despite its giant size, these bones are from a juvenile. Zanno and Makovicky theorize that an adult Siats might have reached the size of Acrocanthosaurus, meaning the two species vie for the second largest predator ever discovered in North America. Tyrannosaurus rex, which holds first place, came along 30 million years later and weighed in at more than twice that amount.

Although Siats and Acrocanthosaurus are both carcharodontosaurs, they belong to different sub-groups. Siats is a member of Neovenatoridae, a more slender-bodied group of carcharodontosaurs. Neovenatorids have been found in Europe, South America, China, Japan and Australia. However, this is the first time a neovenatorid has ever been found in North America.

This newly discovered species, Siats meekerorum, (pronounced see-atch) was the apex predator of its time, and kept tyrannosaurs from assuming top predator roles for millions of years.

Named after a cannibalistic man-eating monster from Ute tribal legend, Siats is a species of carcharodontosaur, a group of giant meat-eaters that includes some of the largest predatory dinosaurs ever discovered. The only other carcharodontosaur known from North America is Acrocanthosaurus, which roamed eastern North America more than 10 million years earlier. Siats is only the second carcharodontosaur ever discovered in North America; Acrocanthosaurus, discovered in 1950, was the first.

"It's been 63 years since a predator of this size has been named from North America," says Lindsay Zanno, a North Carolina State University paleontologist with a joint appointment at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, and lead author of a Nature Communications paper describing the find. "You can't imagine how thrilled we were to see the bones of this behemoth poking out of the hillside."

Zanno and colleague Peter Makovicky, from Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History, discovered the partial skeleton of the new predator in Utah's Cedar Mountain Formation in 2008. The species name acknowledges the Meeker family for its support of early career paleontologists at the Field Museum, including Zanno.

The recovered specimen belonged to an individual that would have been more than 30 feet long and weighed at least four tons. Despite its giant size, these bones are from a juvenile. Zanno and Makovicky theorize that an adult Siats might have reached the size of Acrocanthosaurus, meaning the two species vie for the second largest predator ever discovered in North America. Tyrannosaurus rex, which holds first place, came along 30 million years later and weighed in at more than twice that amount.

Although Siats and Acrocanthosaurus are both carcharodontosaurs, they belong to different sub-groups. Siats is a member of Neovenatoridae, a more slender-bodied group of carcharodontosaurs. Neovenatorids have been found in Europe, South America, China, Japan and Australia. However, this is the first time a neovenatorid has ever been found in North America.

Another Human B.anatomy

Posted Under:

This is another one of human brain anatomy this video was uploaded to education purpose only! so you can get more infos.

New Model of Human Brain

Posted Under:

Hey you can see the parts in the human brain. See and think about human brain parts and their functions as well as.

Brain Anatomy pt-2

Posted Under:

This is part-2 of brain anatomy. So You're able to watch couninously!

Brain Anatomy

Posted Under:

Hello guys! This is about human brain anatomy. It's say about completly in the parts of brain.

Does Obesity Reshape Our Sense of Taste?

Posted Under:

Obesity may alter the way we taste at the most fundamental level: by changing how our tongues react to different foods.

Compared with slimmer counterparts, the plump mice had fewer taste cells that responded to sweet stimuli. What's more, the cells that did respond to sweetness reacted relatively weakly.

The findings peel back a new layer of the mystery of how obesity alters our relationship to food.

What we see is that even at this level -- at the first step in the taste pathway -- the taste receptor cells themselves are affected by obesity," Medler said. "The obese mice have fewer taste cells that respond to sweet stimuli, and they don't respond as well."Medler said it's possible that trouble detecting sweetness may lead obese mice to eat more than their leaner counterparts to get the same payoff.

Learning more about the connection between taste, appetite and obesity is important, she said, because it could lead to new methods for encouraging healthy eating.

The Era of Neutrino Astronomy Has Begun

Posted Under:

Astrophysicists using a telescope embedded in have succeeded in a quest to detect and record the mysterious phenomena known as cosmic neutrinos -- nearly massless particles that stream to Earth at the speed of light from outside our solar system, striking the surface in a burst of energy that can be as powerful as a baseball pitcher's fastball.

Next, they hope to build on the early success of the IceCube Neutrino Observatory to detect the source of these high-energy particles, said Physics Professor Gregory Sullivan, who led the University of Maryland's 12-person team of contributors to the IceCube Collaboration. "The era of neutrino astronomy has begun," Sullivan said as the IceCube Collaboration announced the observation of 28 very high-energy particle events that constitute the first solid evidence for astrophysical neutrinos from cosmic sources.

By studying the neutrinos that IceCube detects, scientists can learn about the nature of astrophysical phenomena occurring millions, or even billions of light years from Earth, Sullivan said.

"The sources of neutrinos, and the question of what could accelerate these particles, has been a mystery for more than 100 years. Now we have an instrument that can detect astrophysical neutrinos. It's working beautifully, and we expect it to run for another 20 years."

The collaboration's report on the first cosmic neutrino records from the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, collected from instruments embedded in one cubic kilometer of ice at the South Pole, was published Nov. 22 in the science.

Next, they hope to build on the early success of the IceCube Neutrino Observatory to detect the source of these high-energy particles, said Physics Professor Gregory Sullivan, who led the University of Maryland's 12-person team of contributors to the IceCube Collaboration. "The era of neutrino astronomy has begun," Sullivan said as the IceCube Collaboration announced the observation of 28 very high-energy particle events that constitute the first solid evidence for astrophysical neutrinos from cosmic sources.

By studying the neutrinos that IceCube detects, scientists can learn about the nature of astrophysical phenomena occurring millions, or even billions of light years from Earth, Sullivan said.

"The sources of neutrinos, and the question of what could accelerate these particles, has been a mystery for more than 100 years. Now we have an instrument that can detect astrophysical neutrinos. It's working beautifully, and we expect it to run for another 20 years."

The collaboration's report on the first cosmic neutrino records from the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, collected from instruments embedded in one cubic kilometer of ice at the South Pole, was published Nov. 22 in the science.

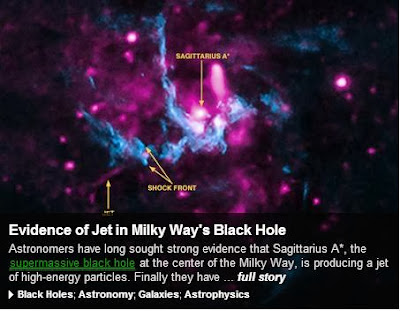

Evidence of Jet in Milky Way's Black Hole

Posted Under:

Hey do you know Astronomers have long sought strong evidence that Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), center of the milky way at the center of the Milky Way, is producing a jet of high-energy particles. Finally they have found it, in new results from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the National Science Foundation's Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope.

The study shows the spin axis of Sgr A* is pointing in one direction, parallel to the rotation axis of the Milky Way, which indicates to astronomers that gas and dust have migrated steadily into Sgr A* over the past 10 billion years. If the Milky Way had collided with large galaxies in the recent past and their central black holes had merged with Sgr A*, the jet could point in any direction.

The jet appears to be running into gas near Sgr A*, producing X-rays detected by Chandra and radio emission observed by the VLA. The two key pieces of evidence for the jet are a straight line of X-ray emitting gas that points toward Sgr A* and a shock front -- similar to a sonic boom -- seen in...

The study shows the spin axis of Sgr A* is pointing in one direction, parallel to the rotation axis of the Milky Way, which indicates to astronomers that gas and dust have migrated steadily into Sgr A* over the past 10 billion years. If the Milky Way had collided with large galaxies in the recent past and their central black holes had merged with Sgr A*, the jet could point in any direction.

The jet appears to be running into gas near Sgr A*, producing X-rays detected by Chandra and radio emission observed by the VLA. The two key pieces of evidence for the jet are a straight line of X-ray emitting gas that points toward Sgr A* and a shock front -- similar to a sonic boom -- seen in...

Neanderthal Viruses Found in Modern Humans

Posted Under:

Ancient viruses from Neanderthals have been found in modern human DNA by researchers at Oxford University and another university.

Around 8% of human DNA is made up of 'endogenous retroviruses' (ERVs), DNA sequences from viruses which pass from generation to generation. This is part of the 90% of our DNA with no known function, sometimes called 'junk' DNA.

'I wouldn't write it off as "junk" just because we don't know what it does yet,' said Dr Gkikas Magiorkinis, an MRC Fellow at Oxford University's Department of Zoology. 'Under certain circumstances, two "junk" viruses can combine to cause disease -- we've seen this many times in animals already. ERVs have been shown to cause cancer when activated by bacteria in mice with weakened immune systems.'

Dr Gkikas and colleagues are now looking to further investigate these ancient viruses, belonging to the HML2 family of viruses, for possible links with cancer and HIV.

'How HIV patients respond to HML2 is related to how fast a patient will progress to AIDS, so there is clearly a connection there,' said Dr Magiorkinis, co-author of the latest study. 'HIV patients are also at much higher risk of developing cancer, for reasons that are poorly-understood. It is possible that some of the risk factors are genetic, and may be shared with HML2. They also become reactivated in cancer and HIV infection, so might prove useful as a therapy target in the future.'

Around 8% of human DNA is made up of 'endogenous retroviruses' (ERVs), DNA sequences from viruses which pass from generation to generation. This is part of the 90% of our DNA with no known function, sometimes called 'junk' DNA.

'I wouldn't write it off as "junk" just because we don't know what it does yet,' said Dr Gkikas Magiorkinis, an MRC Fellow at Oxford University's Department of Zoology. 'Under certain circumstances, two "junk" viruses can combine to cause disease -- we've seen this many times in animals already. ERVs have been shown to cause cancer when activated by bacteria in mice with weakened immune systems.'

Dr Gkikas and colleagues are now looking to further investigate these ancient viruses, belonging to the HML2 family of viruses, for possible links with cancer and HIV.

'How HIV patients respond to HML2 is related to how fast a patient will progress to AIDS, so there is clearly a connection there,' said Dr Magiorkinis, co-author of the latest study. 'HIV patients are also at much higher risk of developing cancer, for reasons that are poorly-understood. It is possible that some of the risk factors are genetic, and may be shared with HML2. They also become reactivated in cancer and HIV infection, so might prove useful as a therapy target in the future.'

Introduction to Male Reproductive Anatomy - Part 3 - The Penis

Posted Under:

Introduction to Male Reproductive Anatomy - Part 3 - The Penis. i hope it will helpful to you 3D anatomy tutorial on the basic anatomical structure of the penis, using the BioDigital Human

Introduction to Male Reproductive Anatomy - Part 2 - Vas Deferent

Posted Under:

You can understand about this "Introduction to Male Reproductive Anatomy - Part 2 - Vas Deferen"This tutorials covers the vas (ductus) deferens, the prostate gland, the seminal vesicles, the bulbourethral glands, and the different parts of the urethra.

Introduction to Male Reproductive Anatomy - Part 1 - Testis

Posted Under:

This is about Introduction to Male Reproductive Anatomy - Part 1 - Testis , It will clear your doubts about this topic! So it will continue...

Circle of Willis - 3D Anatomy Tutorial

Posted Under:

Hey! This is Circle of Willis - 3D Anatomy Tutorial will helpful to you and medical students and doctors.

Modern Bacteria Can Add DNA from Creatures Long-Dead to Its Own

Posted Under:

From a bacteria’s perspective the environment is one big DNA waste yard. Researchers have now shown that bacteria can take up small as well as large pieces of old DNA from this scrapheap and include it in their own genome. This discovery may have major consequences – both in connection with resistance to antibiotics in hospitals and in our perception of the evolution of itself.

Furthermore old DNA is not limited to only returning microbes to earlier states. Damaged DNA can also create new combinations of already functional sequences. You can compare it to a bunch of bacteria which poke around a trash pile looking for fragments they can use. Occasionally they hit some ‘second-hand gold’, which they can use right away. At other times they run the risk of cutting themselves up. It goes both ways. This discovery has a number of consequences partially because there is a potential risk for people when pathogen bacteria or multi-resistant bacteria exchange small fragments of ‘dangerous’ DNA e.g. at hospitals, in biological waste and in waste water.

In the grand perspective the bacteria’s uptake of short DNA represents a fundamental evolutionary process that only needs a growing cell consuming DNA pieces. A process that possibly is a kind of original type of gene-transfer or DNA-sharing between bacteria. The results show how genetic evolution can happen in jerks in small units. The meaning of this is great for our understanding of how microorganisms have exchanged genes through the history of life. The new results also support the theories about gene-transfer as a decisive factor in life’s early evolution.

Søren Overballe-Petersen explains: "This is one of the most exciting perspectives of our discovery. Computer simulations have shown that even early bacteria on Earth had the ability to share DNA – but it was hard to see how it could happen. Now we suggest how the first bacteria exchanged DNA. It is not even a mechanism developed to this specific purpose but rather as a common process, which is a consequence of living and dying."

Furthermore old DNA is not limited to only returning microbes to earlier states. Damaged DNA can also create new combinations of already functional sequences. You can compare it to a bunch of bacteria which poke around a trash pile looking for fragments they can use. Occasionally they hit some ‘second-hand gold’, which they can use right away. At other times they run the risk of cutting themselves up. It goes both ways. This discovery has a number of consequences partially because there is a potential risk for people when pathogen bacteria or multi-resistant bacteria exchange small fragments of ‘dangerous’ DNA e.g. at hospitals, in biological waste and in waste water.

In the grand perspective the bacteria’s uptake of short DNA represents a fundamental evolutionary process that only needs a growing cell consuming DNA pieces. A process that possibly is a kind of original type of gene-transfer or DNA-sharing between bacteria. The results show how genetic evolution can happen in jerks in small units. The meaning of this is great for our understanding of how microorganisms have exchanged genes through the history of life. The new results also support the theories about gene-transfer as a decisive factor in life’s early evolution.

Søren Overballe-Petersen explains: "This is one of the most exciting perspectives of our discovery. Computer simulations have shown that even early bacteria on Earth had the ability to share DNA – but it was hard to see how it could happen. Now we suggest how the first bacteria exchanged DNA. It is not even a mechanism developed to this specific purpose but rather as a common process, which is a consequence of living and dying."

Amber Provides New Insights Into the Evolution of Earth's Atmosphere: Low Oxygen Levels for Dinosaurs

Posted Under:

Hey,An international team of researchers led by Ralf Tappert, University of Innsbruck, reconstructed the composition of Earth's atmosphere of the last 220 million years by analyzing modern and fossil plant resins. The results suggest that atmospheric oxygen was considerably lower in Earth's geological past than previously assumed.

The study has been published in the journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. The interdisciplinary team, consisting of mineralogists, paleontologists and geochemists, use the preserving properties of plant resins, caused by polymerization, for their study. "During photosynthesis plants bind atmospheric carbon, whose isotopic composition is preserved in resins over millions of years, and from this, we can infer atmospheric oxygen concentrations," explains Ralf Tappert. The information about oxygen concentration comes from the isotopic composition of carbon or rather from the ratio between the stable

The study has been published in the journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. The interdisciplinary team, consisting of mineralogists, paleontologists and geochemists, use the preserving properties of plant resins, caused by polymerization, for their study. "During photosynthesis plants bind atmospheric carbon, whose isotopic composition is preserved in resins over millions of years, and from this, we can infer atmospheric oxygen concentrations," explains Ralf Tappert. The information about oxygen concentration comes from the isotopic composition of carbon or rather from the ratio between the stable

Why Men's Noses Are Bigger Than Women's

Posted Under:

Hello freinds do you know...Human noses come in all shapes and sizes. But one feature seems to hold true: Men's noses are bigger than women's

oxygen for muscle tissue growth and maintenance. Larger noses mean more oxygen can be breathed in and transported in the blood to supply the muscle.

It also explains why our noses are smaller than those of our ancestors, such as the Neanderthals. The reason, the researchers believe, is because our distant lineages had more muscle mass, and so needed larger noses to maintain that muscle. Modern humans have less lean muscle mass, meaning we can get away with smaller noses.

"So, in humans, the nose can become small, because our bodies have smaller oxygen requirements than we see in archaic humans," Holton says, noting also that the rib cages and lungs are smaller in modern humans, reinforcing the idea that we don't need as much oxygen to feed our frames as our ancestors. "This all tells us physiologically how modern humans have changed from their ancestors."

Holton and his team tracked nose size and growth of 38 individuals of European descent enrolled in the Iowa Facial Growth Study from three years of age until the mid-twenties, taking external and internal measurements at regular intervals for each individual. The researchers found that boys and girls have the same nose size

oxygen for muscle tissue growth and maintenance. Larger noses mean more oxygen can be breathed in and transported in the blood to supply the muscle.

It also explains why our noses are smaller than those of our ancestors, such as the Neanderthals. The reason, the researchers believe, is because our distant lineages had more muscle mass, and so needed larger noses to maintain that muscle. Modern humans have less lean muscle mass, meaning we can get away with smaller noses.

"So, in humans, the nose can become small, because our bodies have smaller oxygen requirements than we see in archaic humans," Holton says, noting also that the rib cages and lungs are smaller in modern humans, reinforcing the idea that we don't need as much oxygen to feed our frames as our ancestors. "This all tells us physiologically how modern humans have changed from their ancestors."

Holton and his team tracked nose size and growth of 38 individuals of European descent enrolled in the Iowa Facial Growth Study from three years of age until the mid-twenties, taking external and internal measurements at regular intervals for each individual. The researchers found that boys and girls have the same nose size

The Circulatory Song!

Posted Under:

Hello freinda and fans This song is really funny and we heard/watched it for the first time in science which was part of our human biology unit! If you actually learn to memorize it it can be really helpful! LOL! So hope you enjoy!

Oxygen Movement from Alveoli to Capillaries

Posted Under:

Another this one for you....Watch as a molecule of oxygen makes its way from the alveoli (gas layer) through various liquid layers in order to end up in the blood. Rishi is a pediatric infectious disease physician and works at Khan Academy. These videos do not provide medical advice and are for informational purposes only. The videos are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of a qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read or seen in any Khan Academy video

Central Chemoreceptors

Posted Under:

Hey this is about...Central Chemoreceptors!WHat about these..Find out how the your body uses special cells that are central to the brain (inside the brain) to sense levels of CO2 and pH. Rishi is a pediatric infectious disease physician and works at Khan Academy. These videos do not provide medical advice and are for informational purposes only. The videos are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of a qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read or seen in any Khan Academy video.

The Respiratory Center

Posted Under:

Hello freinds! Find out how the respiratory center collects information from all over the body and then helps regulate your breathing. Rishi is a pediatric infectious disease physician and works at Khan Academy. These videos do not provide medical advice and are for informational purposes only. The videos are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of a qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read or seen in any Khan Academy video

New Insights Into Brain Neuronal Networks

Posted Under:

Hello...hey did you know?A paper published in a special edition of the journal Science proposes a novel understanding of brain architecture using a network representation of connections within the primate cortex. Zoltán Toroczkai, professor of physics at the University of Notre Dame and co-director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Network Science and Applications, is a co-author of the paper "Cortical High-Density Counterstream Architectures."

Using brain-wide and consistent tracer data, the researchers describe the cortex as a network of connections with a "bow tie" structure characterized by a high-efficiency, dense core connecting with "wings" of feed-forward and feedback pathways to the rest of the cortex (periphery). The local circuits, reaching to within 2.5 millimeters and taking up more than 70 percent of all the connections in the macaque cortex, are integrated across areas with different functional modalities (somatosensory, motor, cognitive) with medium- to long-range projections.

The authors also report on a simple network model that incorporates the physical principle of entropic cost to long wiring and the spatial positioning of the functional areas in the cortex. They show that this model reproduces the properties of the connectivity data in the experiments, including the structure of the bow tie. The wings of the bow tie emerge from the counterstream organization of the feed-forward and feedback nature of the pathways. They also demonstrate that, contrary to previous beliefs, such high-density cortical graphs can achieve simultaneously strong connectivity (almost direct between any two areas), communication efficiency, and economy of connections (shown via optimizing total wire cost) via weight-distance correlations that are also consequences of this simple network model.

This bow tie arrangement is a typical feature of self-organizing information processing systems. The paper notes that the cortex has some analogies with information-processing networks such as the World Wide Web, as well as metabolism, the immune system and cell signaling. The core-periphery bow tie structure, they say, is "an evolutionarily favored structure for a wide variety of complex networks" because "these systems are not in thermodynamic equilibrium and are required to maintain energy and matter flow through the system." The brain, however, also shows important differences from such systems. For example, destination addresses are encoded in information packets sent along the Internet, apparently unlike in the brain, and location and timing of activity are critical factors of information processing in the brain, unlike in the Internet.

"Biological data is extremely complex and diverse," Toroczkai said. "However, as a physicist, I am interested in what is common or invariant in the data, because it may reveal a fundamental organizational principle behind a complex system. A minimal theory that incorporates such principle should reproduce the observations, if not in great detail, but in extent. I believe that with additional consistent data, as those obtained by the Kennedy team, the fundamental principles of massive information processing in brain neuronal networks are within reach."

Using brain-wide and consistent tracer data, the researchers describe the cortex as a network of connections with a "bow tie" structure characterized by a high-efficiency, dense core connecting with "wings" of feed-forward and feedback pathways to the rest of the cortex (periphery). The local circuits, reaching to within 2.5 millimeters and taking up more than 70 percent of all the connections in the macaque cortex, are integrated across areas with different functional modalities (somatosensory, motor, cognitive) with medium- to long-range projections.

The authors also report on a simple network model that incorporates the physical principle of entropic cost to long wiring and the spatial positioning of the functional areas in the cortex. They show that this model reproduces the properties of the connectivity data in the experiments, including the structure of the bow tie. The wings of the bow tie emerge from the counterstream organization of the feed-forward and feedback nature of the pathways. They also demonstrate that, contrary to previous beliefs, such high-density cortical graphs can achieve simultaneously strong connectivity (almost direct between any two areas), communication efficiency, and economy of connections (shown via optimizing total wire cost) via weight-distance correlations that are also consequences of this simple network model.

This bow tie arrangement is a typical feature of self-organizing information processing systems. The paper notes that the cortex has some analogies with information-processing networks such as the World Wide Web, as well as metabolism, the immune system and cell signaling. The core-periphery bow tie structure, they say, is "an evolutionarily favored structure for a wide variety of complex networks" because "these systems are not in thermodynamic equilibrium and are required to maintain energy and matter flow through the system." The brain, however, also shows important differences from such systems. For example, destination addresses are encoded in information packets sent along the Internet, apparently unlike in the brain, and location and timing of activity are critical factors of information processing in the brain, unlike in the Internet.

"Biological data is extremely complex and diverse," Toroczkai said. "However, as a physicist, I am interested in what is common or invariant in the data, because it may reveal a fundamental organizational principle behind a complex system. A minimal theory that incorporates such principle should reproduce the observations, if not in great detail, but in extent. I believe that with additional consistent data, as those obtained by the Kennedy team, the fundamental principles of massive information processing in brain neuronal networks are within reach."

Is Global Heating Hiding out in the Oceans? Parts of Pacific Warming 15 Times Faster Than in Past 10,000 Years

Posted Under:

Hey do you know?A recent slowdown in global warming has led some skeptics to renew their claims that industrial carbon emissions are not causing a century-long rise in Earth's surface temperatures. But rather than letting humans off the hook, a new study in the leading journal Science adds support to the idea that the oceans are taking up some of the excess heat, at least for the moment. In a reconstruction of Pacific Ocean temperatures in the last 10,000 years, researchers have found that its middle depths have warmed 15 times faster in the last 60 years than they did during apparent natural warming cycles in the previous 10,000.

"We're experimenting by putting all this heat in the ocean without quite knowing how it's going to come back out and affect climate," said study coauthor Braddock Linsley, a climate scientist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "It's not so much the magnitude of the change, but the rate of change."

In its latest report, released in September, the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted the recent slowdown in the rate of global warming. While global temperatures rose by about one-fifth of a degree Fahrenheit per decade from the 1950s through 1990s, warming slowed to just half that rate after the record hot year of 1998. The IPCC has attributed the pause to natural climate fluctuations caused by volcanic eruptions, changes in solar intensity, and the movement of heat through the ocean. Many scientists note that 1998 was an exceptionally hot year even by modern standards, and so any average rise using it as a starting point would downplay the longer-term warming trend.

The IPCC scientists agree that much of the heat that humans have put into the atmosphere since the 1970s through greenhouse gas emissions probably has been absorbed by the ocean. However, the findings in Science put this idea into a long-term context, and suggest that the oceans may be storing even more of the effects of human emissions than scientists have so far realized. "We may have underestimated the efficiency of the oceans as a storehouse for heat and energy," said study lead author, Yair Rosenthal, a climate scientist at Rutgers University. "It may buy us some time -- how much time, I don't really know. But it's not going to stop climate change."

Ocean heat is typically measured from buoys dispersed throughout the ocean, and with instruments lowered from ships, with reliable records at least in some places going back to the 1960s. To look back farther in time, scientists have developed ways to analyze the chemistry of ancient marine life to reconstruct the climates in which they lived. In a 2003 expedition to Indonesia, the researchers collected cores of sediment from the seas where water from the Pacific flows into the Indian Ocean. By measuring the levels of magnesium to calcium in the shells of Hyalinea balthica, a one-celled organism buried in those sediments, the researchers estimated the temperature of the middle-depth waters where H. Balthica lived, from about 1,500 to 3,000 feet down. The temperature record there reflects middle-depth temperatures throughout the western Pacific, the researchers say, since the waters around Indonesia originate from the mid-depths of the North and South Pacific.

Though the climate of the last 10,000 years has been thought to be relatively stable, the researchers found that the Pacific intermediate depths have generally been cooling during that time, though with various ups and downs. From about 7,000 years ago until the start of the Medieval Warm Period in northern Europe, at about 1100, the water cooled gradually, by almost 1 degree C, or almost 2 degrees F. The rate of cooling then picked up during the so-called Little Ice Age that followed, dropping another 1 degree C, or 2 degrees F, until about 1600. The authors attribute the cooling from 7,000 years ago until the Medieval Warm Period to changes in Earth's orientation toward the sun, which affected how much sunlight fell on both poles. In 1600 or so, temperatures started gradually going back up. Then, over the last 60 years, water column temperatures, averaged from the surface to 2,200 feet, increased 0.18 degrees C, or .32 degrees F. That might seem small in the scheme of things, but it's a rate of warming 15 times faster than at any period in the last 10,000 years, said Linsley.

One explanation for the recent slowdown in global warming is that a prolonged La Niña-like cooling of eastern Pacific surface waters has helped to offset the global rise in temperatures from greenhouse gases. In a study in the journal Nature in August, climate modelers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography showed that La Niña cooling in the Pacific seemed to suppress global average temperatures during northern hemisphere winters but allowed temperatures to rise during northern hemisphere summers, explaining last year's record U.S. heat wave and the ongoing loss of Arctic sea ice.

When the La Niña cycle switches, and the Pacific reverts to a warmer than usual El Niño phase, global temperatures may likely shoot up again, along with the rate of warming. "With global warming you don't see a gradual warming from one year to the next," said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., who was not involved in the research. "It's more like a staircase. You trot along with nothing much happening for 10 years and then suddenly you have a jump and things never go back to the previous level again."

The study's long-term perspective suggests that the recent pause in global warming may just reflect random variations in heat going between atmosphere and ocean, with little long-term importance, says Drew Shindell, a climate scientist with joint appointments at Columbia's Earth Institute and the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and a lead author on the latest IPCC report. "Surface temperature is only one indicator of climate change," he said. "Looking at the total energy stored by the climate system or multiple indicators--glacier melting, water vapor in the atmosphere, snow cover, and so on -- may be more useful than looking at surface temperature alone."

"We're experimenting by putting all this heat in the ocean without quite knowing how it's going to come back out and affect climate," said study coauthor Braddock Linsley, a climate scientist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "It's not so much the magnitude of the change, but the rate of change."

In its latest report, released in September, the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted the recent slowdown in the rate of global warming. While global temperatures rose by about one-fifth of a degree Fahrenheit per decade from the 1950s through 1990s, warming slowed to just half that rate after the record hot year of 1998. The IPCC has attributed the pause to natural climate fluctuations caused by volcanic eruptions, changes in solar intensity, and the movement of heat through the ocean. Many scientists note that 1998 was an exceptionally hot year even by modern standards, and so any average rise using it as a starting point would downplay the longer-term warming trend.

The IPCC scientists agree that much of the heat that humans have put into the atmosphere since the 1970s through greenhouse gas emissions probably has been absorbed by the ocean. However, the findings in Science put this idea into a long-term context, and suggest that the oceans may be storing even more of the effects of human emissions than scientists have so far realized. "We may have underestimated the efficiency of the oceans as a storehouse for heat and energy," said study lead author, Yair Rosenthal, a climate scientist at Rutgers University. "It may buy us some time -- how much time, I don't really know. But it's not going to stop climate change."

Ocean heat is typically measured from buoys dispersed throughout the ocean, and with instruments lowered from ships, with reliable records at least in some places going back to the 1960s. To look back farther in time, scientists have developed ways to analyze the chemistry of ancient marine life to reconstruct the climates in which they lived. In a 2003 expedition to Indonesia, the researchers collected cores of sediment from the seas where water from the Pacific flows into the Indian Ocean. By measuring the levels of magnesium to calcium in the shells of Hyalinea balthica, a one-celled organism buried in those sediments, the researchers estimated the temperature of the middle-depth waters where H. Balthica lived, from about 1,500 to 3,000 feet down. The temperature record there reflects middle-depth temperatures throughout the western Pacific, the researchers say, since the waters around Indonesia originate from the mid-depths of the North and South Pacific.

Though the climate of the last 10,000 years has been thought to be relatively stable, the researchers found that the Pacific intermediate depths have generally been cooling during that time, though with various ups and downs. From about 7,000 years ago until the start of the Medieval Warm Period in northern Europe, at about 1100, the water cooled gradually, by almost 1 degree C, or almost 2 degrees F. The rate of cooling then picked up during the so-called Little Ice Age that followed, dropping another 1 degree C, or 2 degrees F, until about 1600. The authors attribute the cooling from 7,000 years ago until the Medieval Warm Period to changes in Earth's orientation toward the sun, which affected how much sunlight fell on both poles. In 1600 or so, temperatures started gradually going back up. Then, over the last 60 years, water column temperatures, averaged from the surface to 2,200 feet, increased 0.18 degrees C, or .32 degrees F. That might seem small in the scheme of things, but it's a rate of warming 15 times faster than at any period in the last 10,000 years, said Linsley.

One explanation for the recent slowdown in global warming is that a prolonged La Niña-like cooling of eastern Pacific surface waters has helped to offset the global rise in temperatures from greenhouse gases. In a study in the journal Nature in August, climate modelers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography showed that La Niña cooling in the Pacific seemed to suppress global average temperatures during northern hemisphere winters but allowed temperatures to rise during northern hemisphere summers, explaining last year's record U.S. heat wave and the ongoing loss of Arctic sea ice.

When the La Niña cycle switches, and the Pacific reverts to a warmer than usual El Niño phase, global temperatures may likely shoot up again, along with the rate of warming. "With global warming you don't see a gradual warming from one year to the next," said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., who was not involved in the research. "It's more like a staircase. You trot along with nothing much happening for 10 years and then suddenly you have a jump and things never go back to the previous level again."

The study's long-term perspective suggests that the recent pause in global warming may just reflect random variations in heat going between atmosphere and ocean, with little long-term importance, says Drew Shindell, a climate scientist with joint appointments at Columbia's Earth Institute and the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and a lead author on the latest IPCC report. "Surface temperature is only one indicator of climate change," he said. "Looking at the total energy stored by the climate system or multiple indicators--glacier melting, water vapor in the atmosphere, snow cover, and so on -- may be more useful than looking at surface temperature alone."

Surprising Variation Among Genomes of Individual Neurons from Same Brain

Posted Under:

Hey It was once thought that each cell in a person's body possesses the same DNA code and that the particular way the genome is read imparts cell function and defines the individual. For many cell types in our bodies, however, that is an oversimplification. Studies of neuronal genomes published in the past decade have turned up extra or missing chromosomes, or pieces of DNA that can copy and paste themselves throughout the genomes.

The only way to know for sure that neurons from the same person harbor unique DNA is by profiling the genomes of single cells instead of bulk cell populations, the latter of which produce an average. Now, using single-cell sequencing, Salk Institute researchers and their collaborators have shown that the genomic structures of individual neurons differ from each other even more than expected. The findings were published November 1 in Science.

"Contrary to what we once thought, the genetic makeup of neurons in the brain aren't identical, but are made up of a patchwork of DNA," says corresponding author Fred Gage, Salk's Vi and John Adler Chair for Research on Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease.

In the study, led by Mike McConnell, a former junior fellow in the Crick-Jacobs Center for Theoretical and Computational Biology at the Salk, researchers isolated about 100 neurons from three people posthumously. The scientists took a high-level view of the entire genome -- -- looking for large deletions and duplications of DNA called copy number variations or CNVs -- -- and found that as many as 41 percent of neurons had at least one unique, massive CNV that arose spontaneously, meaning it wasn't passed down from a parent. The CNVs are spread throughout the genome, the team found.

The miniscule amount of DNA in a single cell has to be chemically amplified many times before it can be sequenced. This process is technically challenging, so the team spent a year ruling out potential sources of error in the process.

"A good bit of our study was doing control experiments to show that this is not an artifact," says Gage. "We had to do that because this was such a surprise -- -- finding out that individual neurons in your brain have different DNA content."

The group found a similar amount of variability in CNVs within individual neurons derived from the skin cells of three healthy people. Scientists routinely use such induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to study living neurons in a culture dish. Because iPSCs are derived from single skin cells, one might expect their genomes to be the same.

"The surprising thing is that they're not," says Gage. "There are quite a few unique deletions and amplifications in the genomes of neurons derived from one iPSC line."

Interestingly, the skin cells themselves are genetically different, though not nearly as much as the neurons. This finding, along with the fact that the neurons had unique CNVs, suggests that the genetic changes occur later in development and are not inherited from parents or passed to offspring.

It makes sense that neurons have more diverse genomes than skin cells do, says McConnell, who is now an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the University of Virginia School of Medicine in Charlottesville. "The thing about neurons is that, unlike skin cells, they don't turn over, and they interact with each other," he says. "They form these big complex circuits, where one cell that has CNVs that make it different can potentially have network-wide influence in a brain."

Spontaneously occurring CNVs have also been linked to risk for brain disorders such as schizophrenia and autism, but those studies usually pool many blood cells. As a result, the CNVs uncovered in those studies affect many if not all cells, which suggests that they arise early in development.

The purpose of CNVs in the healthy brain is still unclear, but researchers have some ideas. The modifications might help people adapt to new surroundings encountered over a lifetime, or they might help us survive a massive viral infection. The scientists are working out ways to alter genomic variability in iPSC-derived neurons and challenge them in specific ways in the culture dish.

Cells with different genomes probably produce unique RNA and then proteins. However, for now, only one sequencing technology can be applied to a single cell.

"If and when more than one method can be applied to a cell, we will be able to see whether cells with different genomes have different transcriptomes (the collection of all the RNA in a cell) in predictable ways," says McConnell.

In addition, it will be necessary to sequence many more cells, and in particular, more cell types, notes corresponding author Ira Hall, an associate professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the University of Virginia. "There's a lot more work to do to really understand to what level we think the things we've found are neuron-specific or associated with different parameters like age or genotype," he says.

Other authors on the study are Michael Lindberg and Svetlana Shumilina of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics at the University of Virginia School of Medicine; Kristen Brennand, now at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York; Julia Piper, now at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Thierry Voet and Joris Vermeesch of the Center for Human Genetics, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Chris Cowing-Zitron of Salk's Laboratory of Genetics; and Roger Lasken of the J. Craig Venter Institute in San Diego.

This work was supported by the Crick-Jacobs Center for Theoretical and Computational Biology, the G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the JPB Foundation, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

The only way to know for sure that neurons from the same person harbor unique DNA is by profiling the genomes of single cells instead of bulk cell populations, the latter of which produce an average. Now, using single-cell sequencing, Salk Institute researchers and their collaborators have shown that the genomic structures of individual neurons differ from each other even more than expected. The findings were published November 1 in Science.

"Contrary to what we once thought, the genetic makeup of neurons in the brain aren't identical, but are made up of a patchwork of DNA," says corresponding author Fred Gage, Salk's Vi and John Adler Chair for Research on Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease.

In the study, led by Mike McConnell, a former junior fellow in the Crick-Jacobs Center for Theoretical and Computational Biology at the Salk, researchers isolated about 100 neurons from three people posthumously. The scientists took a high-level view of the entire genome -- -- looking for large deletions and duplications of DNA called copy number variations or CNVs -- -- and found that as many as 41 percent of neurons had at least one unique, massive CNV that arose spontaneously, meaning it wasn't passed down from a parent. The CNVs are spread throughout the genome, the team found.

The miniscule amount of DNA in a single cell has to be chemically amplified many times before it can be sequenced. This process is technically challenging, so the team spent a year ruling out potential sources of error in the process.

"A good bit of our study was doing control experiments to show that this is not an artifact," says Gage. "We had to do that because this was such a surprise -- -- finding out that individual neurons in your brain have different DNA content."

The group found a similar amount of variability in CNVs within individual neurons derived from the skin cells of three healthy people. Scientists routinely use such induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to study living neurons in a culture dish. Because iPSCs are derived from single skin cells, one might expect their genomes to be the same.

"The surprising thing is that they're not," says Gage. "There are quite a few unique deletions and amplifications in the genomes of neurons derived from one iPSC line."

Interestingly, the skin cells themselves are genetically different, though not nearly as much as the neurons. This finding, along with the fact that the neurons had unique CNVs, suggests that the genetic changes occur later in development and are not inherited from parents or passed to offspring.

It makes sense that neurons have more diverse genomes than skin cells do, says McConnell, who is now an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the University of Virginia School of Medicine in Charlottesville. "The thing about neurons is that, unlike skin cells, they don't turn over, and they interact with each other," he says. "They form these big complex circuits, where one cell that has CNVs that make it different can potentially have network-wide influence in a brain."

Spontaneously occurring CNVs have also been linked to risk for brain disorders such as schizophrenia and autism, but those studies usually pool many blood cells. As a result, the CNVs uncovered in those studies affect many if not all cells, which suggests that they arise early in development.

The purpose of CNVs in the healthy brain is still unclear, but researchers have some ideas. The modifications might help people adapt to new surroundings encountered over a lifetime, or they might help us survive a massive viral infection. The scientists are working out ways to alter genomic variability in iPSC-derived neurons and challenge them in specific ways in the culture dish.

Cells with different genomes probably produce unique RNA and then proteins. However, for now, only one sequencing technology can be applied to a single cell.

"If and when more than one method can be applied to a cell, we will be able to see whether cells with different genomes have different transcriptomes (the collection of all the RNA in a cell) in predictable ways," says McConnell.

In addition, it will be necessary to sequence many more cells, and in particular, more cell types, notes corresponding author Ira Hall, an associate professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the University of Virginia. "There's a lot more work to do to really understand to what level we think the things we've found are neuron-specific or associated with different parameters like age or genotype," he says.

Other authors on the study are Michael Lindberg and Svetlana Shumilina of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics at the University of Virginia School of Medicine; Kristen Brennand, now at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York; Julia Piper, now at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Thierry Voet and Joris Vermeesch of the Center for Human Genetics, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Chris Cowing-Zitron of Salk's Laboratory of Genetics; and Roger Lasken of the J. Craig Venter Institute in San Diego.

This work was supported by the Crick-Jacobs Center for Theoretical and Computational Biology, the G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the JPB Foundation, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Fossil of Largest Known Platypus Discovered in Australia

Posted Under:

Hey do you know?No living mammal is more peculiar than the platypus. It has a broad, duck-like bill, thick, otter-like fur, and webbed, beaver-like feet. The platypus lays eggs rather than gives birth to live young, its snout is covered with electroreceptors that detect underwater prey, and male platypuses have a venomous spur on their hind foot. Until recently, the fossil record indicated that the platypus lineage was unique, with only one species inhabiting Earth at any one time. This picture has changed with the publication of a new study in the latest issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology that describes a new, giant species of extinct platypus that was a side-branch of the platypus family tree.

I say about this the new platypus species, named Obdurodon tharalkooschild, is based on a single tooth from the famous Riversleigh World Heritage Area of northwest Queensland. While many of Riversleigh's fossil deposits are now being radiometrically dated, the precise age of the particular deposit that produced this giant platypus is in doubt but is likely to be between 15 and 5 million years old.

"Monotremes (platypuses and echidnas) are the last remnant of an ancient radiation of mammals unique to the southern continents. A new platypus species, even one that is highly incomplete, is a very important aid in developing understanding about these fascinating mammals," said PhD candidate Rebecca Pian, lead author of the study.

Based on the size of tooth, it is estimated that this extinct species would have been nearly a meter (more than three feet) long, twice the size of the modern platypus. The bumps and ridges on the teeth also provide clues about what this species likely ate.

"Like other platypuses, it was probably a mostly aquatic mammal, and would have lived in and around the freshwater pools in the forests that covered the Riversleigh area millions of years ago," said Dr. Suzanne Hand of the University of New South Wales, a co-author of the study. "Obdurodon tharalkooschild was a very large platypus with well-developed teeth, and we think it probably fed not only on crayfish and other freshwater crustaceans, but also on small vertebrates including the lungfish, frogs, and small turtles that are preserved with it in the Two Tree Site fossil deposit."

The oldest platypus fossils come from 61 million-year-old rocks in southern South America. Younger platypus fossils are known from Australia in what is now the Simpson Desert. Before the discovery of Obdurodon tharalkooschild, these fossils suggested that platypuses became smaller and reduced the size of their teeth through time. The modern platypus completely lacks teeth as an adult and instead bears horny pads in its mouth. The name Obdurodon comes from the Greek for "lasting (obdurate) tooth" and was coined to distinguish extinct toothed platypuses from the essentially toothless modern species.

"Discovery of this new species was a shock to us because prior to this, the fossil record suggested that the evolutionary tree of platypuses was relatively linear one," said Dr. Michael Archer of the University of New South Wales, a co-author of the study. "Now we realize that there were unanticipated side branches on this tree, some of which became gigantic."

The specific epithet of the new species, tharalkooschild, honors an Indigenous Australian creation story about the origin of the platypus. In the Dreamtime, Tharalkoo was a head-strong girl duck inclined to disobey her parents. Her parents warned her not to swim downriver because Bigoon the Water-rat would have his wicked way with her. Scoffing, she disobeyed her parents and was ravished by Bigoon. By the time Tharalkoo escaped and returned to her family, the other girl ducks were laying eggs, so she did the same. But instead of a fluffy little duckling emerging from her egg, her child was an amazing chimera that had the bill, webbed hind feet, and egg-laying habit of a duck, along with the fur and front feet of a rodent -- the first Platypus.

I say about this the new platypus species, named Obdurodon tharalkooschild, is based on a single tooth from the famous Riversleigh World Heritage Area of northwest Queensland. While many of Riversleigh's fossil deposits are now being radiometrically dated, the precise age of the particular deposit that produced this giant platypus is in doubt but is likely to be between 15 and 5 million years old.

"Monotremes (platypuses and echidnas) are the last remnant of an ancient radiation of mammals unique to the southern continents. A new platypus species, even one that is highly incomplete, is a very important aid in developing understanding about these fascinating mammals," said PhD candidate Rebecca Pian, lead author of the study.

Based on the size of tooth, it is estimated that this extinct species would have been nearly a meter (more than three feet) long, twice the size of the modern platypus. The bumps and ridges on the teeth also provide clues about what this species likely ate.

"Like other platypuses, it was probably a mostly aquatic mammal, and would have lived in and around the freshwater pools in the forests that covered the Riversleigh area millions of years ago," said Dr. Suzanne Hand of the University of New South Wales, a co-author of the study. "Obdurodon tharalkooschild was a very large platypus with well-developed teeth, and we think it probably fed not only on crayfish and other freshwater crustaceans, but also on small vertebrates including the lungfish, frogs, and small turtles that are preserved with it in the Two Tree Site fossil deposit."

The oldest platypus fossils come from 61 million-year-old rocks in southern South America. Younger platypus fossils are known from Australia in what is now the Simpson Desert. Before the discovery of Obdurodon tharalkooschild, these fossils suggested that platypuses became smaller and reduced the size of their teeth through time. The modern platypus completely lacks teeth as an adult and instead bears horny pads in its mouth. The name Obdurodon comes from the Greek for "lasting (obdurate) tooth" and was coined to distinguish extinct toothed platypuses from the essentially toothless modern species.

"Discovery of this new species was a shock to us because prior to this, the fossil record suggested that the evolutionary tree of platypuses was relatively linear one," said Dr. Michael Archer of the University of New South Wales, a co-author of the study. "Now we realize that there were unanticipated side branches on this tree, some of which became gigantic."

The specific epithet of the new species, tharalkooschild, honors an Indigenous Australian creation story about the origin of the platypus. In the Dreamtime, Tharalkoo was a head-strong girl duck inclined to disobey her parents. Her parents warned her not to swim downriver because Bigoon the Water-rat would have his wicked way with her. Scoffing, she disobeyed her parents and was ravished by Bigoon. By the time Tharalkoo escaped and returned to her family, the other girl ducks were laying eggs, so she did the same. But instead of a fluffy little duckling emerging from her egg, her child was an amazing chimera that had the bill, webbed hind feet, and egg-laying habit of a duck, along with the fur and front feet of a rodent -- the first Platypus.

Respiratory system with differnt clips

Posted Under:

Hello freinds hes right, the left lung has one less branch. if you notice the right lung has 3 lobes, the left has 2 lobes, and that is due to the missing or absence of one left branch on the left. also, because the heart takes up some space (cardiac notch) where the 3rd lobe would of been

Cellular Respiration

Posted Under:

Verny Lopez Nieto explains the respiratory chain in aerobic conditions in the inner mitochondrial membrane. It argues that the process of cellular respiration involves the formation of energy from ATP-APP molecules and explains the formation of NADH and FADH molecules, which are those that carry high-energy electrons. Finally, it explains the formation of potential energy.

Respiratory system

Posted Under:

Hello freinds and fans this is for you It's pretty good explanation, but is clearly not mixed with scientific information. Science studies nature, but it does not make interpretations. Evolution or not does not matter as long evolution to gain a knowledge of nature, but this is religion and no argument given here demonstrates a thorough understanding of the theory of evolution.

Lung Anatomy

Posted Under:

is 3D medical animation begins with a detailed description of the anatomy and physiology of the lungs (Pulmonary system). It describes the pleura and diaphragm which aid in lung expansion. The animation also deals with lung cancer and the role of lymph in transporting bacteria, allergens and cancer cells away from the lungs and to the lymph nodes.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)